Many years ago, I enrolled in a secular medical school following my conversion to Christianity. This school was located in the American South— a very different social and cultural climate than New York City, where I had attended university. The most notable difference to my freshly borne self was the higher population density of Christians; how fortunate, I thought, to be surrounded by brothers and sisters while weathering the storms of academia and meeting death and suffering face-to-face.

It’s a cliche told by us Northerners— perhaps to convince ourselves that our unfriendliness is not only harmless but representative of a virtuous honesty— that Southerners are “fake nice.” I didn’t live in the South long enough to test this hypothesis, but I did notice a preponderance of Christians identifiable by self-assigned label and not by deed.

As an overeager convert, one of my goals in medical school was to create an American, female version of the Inklings (admittedly, I still haven’t assented to my repeated failures in this endeavor, and the goal remains). To this end, I sought out female medical students interested in forming a discipleship triad, finding plenty of women eager to make “Christian friends” and enjoy the warmth of hospitality. But when it came to finding women seemingly dedicated to spiritual maturation, I was grasping at straws. I did, however, manage to grasp two.

As the inaugural reading material for our women’s discipleship triad, I selected Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s The Cost of Discipleship. The more we read, the more the women disagreed with it, and our meetings rapidly came to an end. Our friendships continued, however, as I watched one of the women renounce Christianity for atheism later that year.

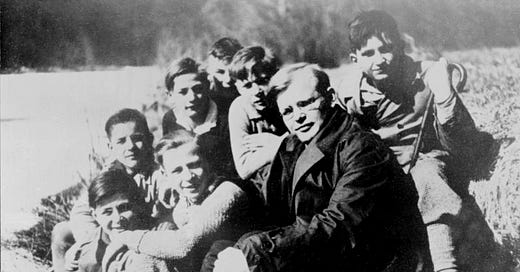

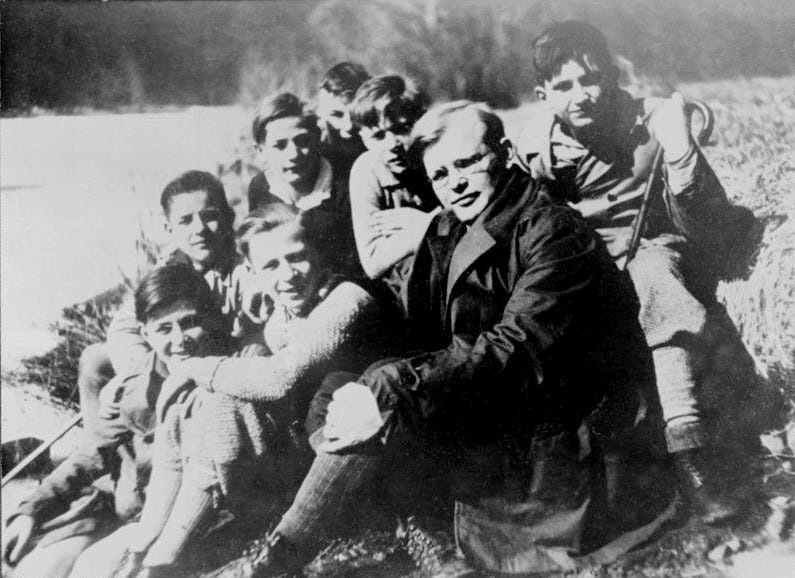

By my estimation, Bonhoeffer’s book is a useful litmus test for ferreting out Christians uncomfortable with sacrifice. The modern translation of this book is that Christianity isn’t a casual hobby. Jesus’s objective wasn’t to transform conditional Southern niceness into an air of moral superiority under the guise of a perjured name. Rather He asks for fealty; He demands allegiance no matter the circumstance. Once a Christian, you can no longer use desire and personal gain as your primary guideposts for action; nor can you decline to surrender what may be dearest to you when the time comes. A Nazi dissident due to his Christian beliefs, Bonhoeffer was hanged by the Nazis; for him, discipleship cost his life. “When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.”1

We are often tricked into thinking that only special Christians are called to be disciples of Jesus— that the Bonhoeffers and Wilberforces of the world are extraordinary people, not that they are mere mortals with extraordinary faith and God-granted courage. The women in my triad ascribed to this belief, rendering Protestantism’s “saved by grace through faith” a cheap statement to exclude concepts such as free will or the fruits of the Spirit in favor of a God who just wants us to love him in our hearts— and to leave our love trapped there. In The Cost of Discipleship, Bonhoeffer formulated the original concept of “cheap grace”:

Cheap grace is the preaching of forgiveness without requiring repentance, baptism without church discipline, Communion without confession, absolution without personal confession. Cheap grace is grace without discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without Jesus Christ, living and incarnate.

The first step in becoming a disciple of Jesus is to “take up [your] cross and follow,” but we forget what the cross represents. In the modern day, moral therapeutic deism tempts us with the comforts of a God without any demands. Cultural Christianity gives us the structure of tradition without the burden of sacrifice. Both belief systems propose that the adherent go to Heaven when he or she dies; but on what authority save wishful thinking? We have no right to ask God to be our Savior without acknowledging Him as our Lord, or without acknowledging the great cost He paid to save us. Bonhoeffer describes genuine, “costly” grace as this:

Costly grace is the treasure hidden in the field; for the sake of it a man will go and sell all that he has. It is the pearl of great price to buy which the merchant will sell all his goods. It is the kingly rule of Christ, for whose sake a man will pluck out the eye which causes him to stumble; it is the call of Jesus Christ at which the disciple leaves his nets and follows him.

Such grace is costly because it calls us to follow, and it is grace because it calls us to follow Jesus Christ. It is costly because it costs a man his life, and it is grace because it gives a man the only true life. It is costly because it condemns sin, and grace because it justifies the sinner. Above all, it is costly because it cost God the life of his Son: "ye were bought at a price," and what has cost God much cannot be cheap for us. Above all, it is grace because God did not reckon his Son too dear a price to pay for our life, but delivered him up for us. Costly grace is the Incarnation of God.

To the reader who replies that none of us behave as perfect disciples, this is true. We are all disobedient, willingly or not, and are fundamentally undeserving of His grace— but there is a vast difference between the repentant sinner who strives to love God with all his heart, soul, and mind, and the willfully disobedient sinner who serves one master: himself. Bonhoeffer calls us to costly grace and yet never forgets that it is grace, and that our virtues manifest downstream:

Fruit is always the miraculous, the created; it is never the result of willing, but always a growth. The fruit of the Spirit is a gift of God, and only He can produce it. They who bear it know as little about it as the tree knows of its fruit. They know only the power of Him on whom their life depends.

I have spoken to non-Christians who are very disturbed— and rightly so— by evil deceivers posing as the faithful elect. We all know that they exist; but we forget that the Maker and Sustainer of all cannot be deceived. Unlike many of us (at least in our hopeful youth), God is not a simpleton won over by gilded tokens of affection. The Ruler of the Universe won’t be tricked into granting eternal salvation to an evil person just because they stand under the roof of a church for two hours every week. Actions have eternal consequences, however seemingly insignificant they may be:

People often think of Christian morality as a kind of bargain in which God says, "If you keep a lot of rules I'll reward you, and if you don't I'll do the other thing." I do not think that is the best way of looking at it. I would much rather say that every time you make a choice you are turning the central part of you, the part of you that chooses, into something a little different from what it was before.

And taking your life as a whole, with all your innumerable choices, all your life long you are slowly turning this central thing either into a heavenly creature or into a hellish creature: either into a creature that is in harmony with God, and with other creatures, and with itself, or else into one that is in a state of war and hatred with God, and with its fellow-creatures, and with itself.2

In closing, it is not our responsibility to judge the state of salvation of another’s soul. That is not what I mean by using Bonhoeffer’s words as a litmus test; that we use them to judge and ostracize those who don’t fall in line with Christian doctrine. On the contrary, we may use the results of our litmus test to better serve our fellow men. If I had trusted my instincts about the women’s spiritual maturity, I would have discipled her with an evangelical bent; as a mentor, not a peer, drawing out her doubts and addressing them with honest vulnerability.

“Take up your cross and follow me.” We are invited to the adventure of a lifetime, an adventure rife with suffering and redeemed by grace, all at a very great cost indeed.

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. The Cost of Discipleship 1st Touchstone ed., Simon and Schuster, 1995.

Lewis, C.S. Mere Christianity, Touchstone: New York, 1996, pp. 87-88.