When I was a university student in New York City, I would often become overwhelmed by the hustle and bustle of our tightly packed campus. But instead of escaping to the natural beauties of Central Park or upstate New York for a much-needed rest, when pressed for time I would ride the Subway to Times Square. When I finally returned to campus, my mental reference point was reset: after tolerating the crowds, advertisements, and grime of Times Square, I perceived my campus as a comparative oasis. The physical contrast helped to reveal its beauty to me, a beauty otherwise hidden by repetitive exposure, distraction, and ingratitude.

This is how I will attempt to help you, my readers, to infer the glories of Christian theism: by contrasting them with irrationality, meaninglessness, and sometimes even horror. I am adapting the phrase “negative apologetics,” which usually refers to a defense against anti-Christian arguments, to describe this tactic. In other words, I will highlight an alternative worldview—one which differs from Christian theism or even opposes it in some way— to reveal by contrast the truth, hope, and beauty contained within Christianity. I hope to write one post in this series every couple of months in between my usual church history-themed writings.

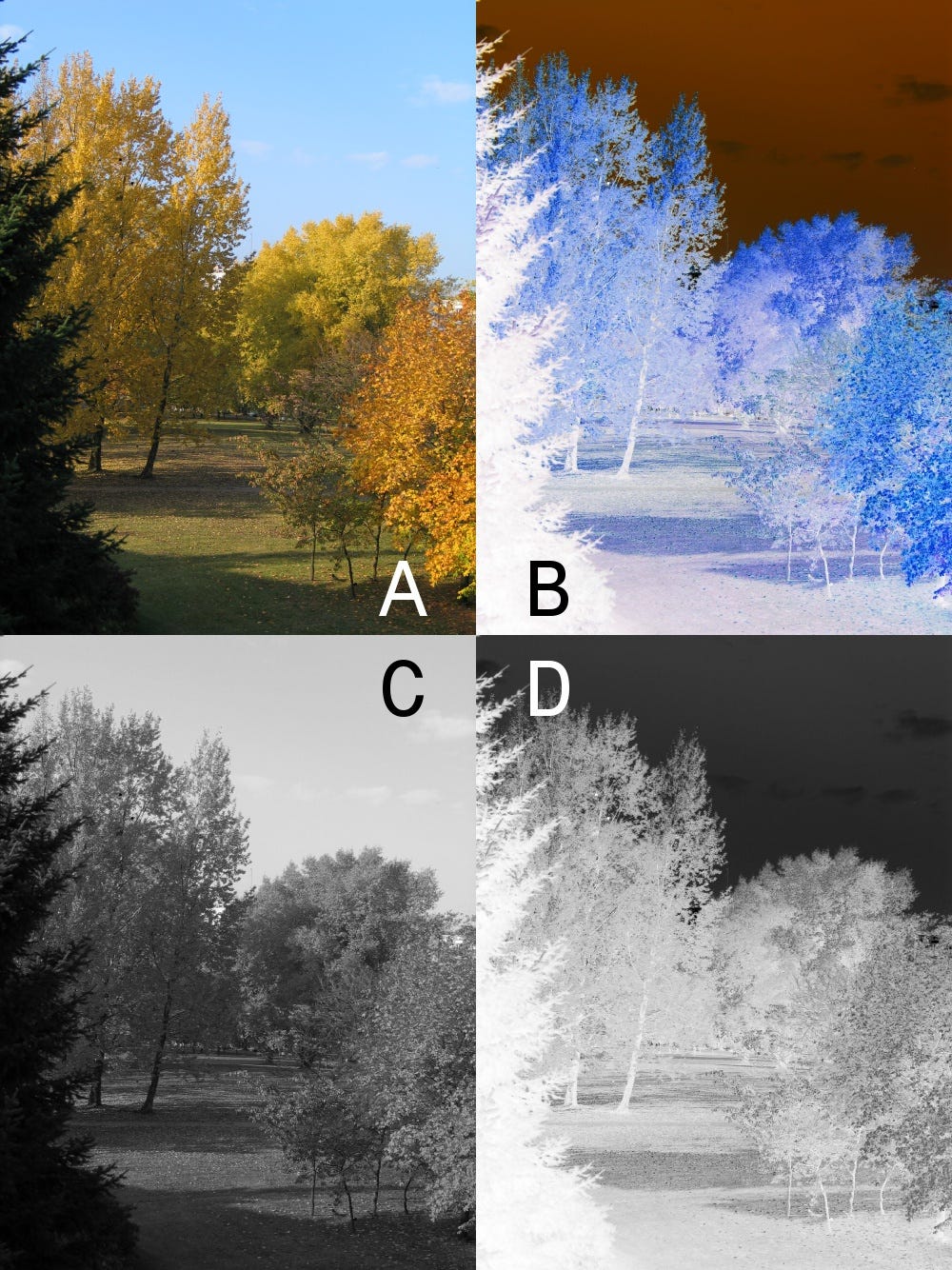

But why call this type of apologetics “negative” if its goal is to showcase Christianity’s virtue? Because, like a photographic negative, it will infer Christianity’s virtue by showing you the undesirable darkness of its opposite. Photographic negatives (figure 1B and D below) are precursors of a final photograph (figure 1A and C below) which represents the reality of the captured image. Negatives are not only the precursors of the final product; they are also the visual opposite of the final product. Bright areas in the original scene will appear as dark ones in the negative, and vice versa; they have a “reversed tonal relationship.” But through the negative you can easily infer the true image.

Of course, there may not exist a worldview which contains the exact opposite of every Christian belief. But there are many belief systems which contradict one or several of Christianity’s key tenets. It’s tempting to view these differences as just theoretical, but absent a complete disconnect between belief and behavior (which many people do have), they manifest as real differences in our manner of living.

Let me provide an example. I recently finished reading Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment1; a long overdue read after Brothers Karamazov. The novel’s protagonist is Rodion Raskolnikov, an ex-university student living in poverty in 19th Century St. Petersburg. He doesn’t believe in God, tradition, or obedience to a moral code; he thinks that rule-followers are cowards and that true courage lies with the man who “dares to stoop and take [power]” for himself. Raskolnikov thus categorizes humans into ordinary and extraordinary classes, the latter of which is defined by the transgression of law and the destruction of the present order for the purpose of progress.

In Christianity, perfect adherence to moral law isn’t a defining characteristic of the weak but of God alone: Jesus practiced unflinching obedience to his Father’s will to save an undeserving people.

Clearly, Raskolnikov’s worldview differs from Christian tenets on multiple levels, not just in its rejection of tradition— so let’s first dive into Crime and Punishment, enjoy some of Dostoevsky’s brilliant quotes, and transform our findings into negative apologia.

A Dissection of Raskolnikov’s Worldview

Midway through the book, we find out that Raskolnikov once wrote an article to describe his worldview and justify his classification of men:

[M]en are in general divided by a law of nature into two categories, inferior (ordinary), that is, so to say, material that serves only to reproduce its kind, and men who have the gift or the talent to utter a new word. […] The first category, generally speaking, are men conservative in temperament and law-abiding; they live under control and love to be controlled. To my thinking it is their duty to be controlled, because that’s their vocation, and there is nothing humiliating in it for them. The second category all transgress the law; they are destroyers or disposed to destruction according to their capacities. The crimes of these men are of course relative and varied; for the most part they seek in very varied ways the destruction of the present for the sake of the better. But if such a one is forced for the sake of his idea to step over a corpse or wade through blood, he can, I maintain, find within himself, in his conscience, a sanction for wading through blood […] The first category is always the man of the present, the second the man of the future. The first preserve the world and people it, the second move the world and lead it to its goal.

At first glance, Raskolnikov’s categorization of men contains a minute grain of truth. There exist men with power and men without, and many powerful men have compromised their morals to some degree during their upward climb. But Dostoevsky doesn’t allow his readers to gloss over Raskolnikov’s philosophy, nor does he allow Raskolnikov to remain detached from it— he forces Raskolnikov to participate in it and live out its consequences.

Raskolnikov’s beliefs play out brutally: imagining himself as an extraordinary man and wanting to see if he is indeed courageous enough to behave like one, Raskolnikov breaks into an old pawnbroker’s apartment and murders her with an axe. When this woman’s sister unexpectedly arrives in the apartment, Raskolnikov murders her also. He ends up stealing a few trinkets from the apartment but doesn’t sell or use them, instead hiding them in an alleyway to throw the police off his trail. Afterwards, unable to stomach what he has done, Raskolnikov falls ill and slips in and out of feverish delusions:

He was not completely unconscious, however, all the time he was ill; he was in a feverish state, sometimes delirious, sometimes half conscious. […] He worried and tormented himself trying to remember, moaned, flew into a rage, or sank into awful, intolerable terror.

It is important to note a few things about the murder before moving forward: first, that Raskolnikov did not benefit economically from the murder and second, that both the choice of victim and the choice of crime were extremely bizarre yet perfectly fitting with Raskolnikov’s worldview and goal. The old woman was deemed a disposable member of the ordinary class (“a useless, loathsome, harmful creature”) and the murder was deemed a daring act by which Raskolnikov could prove his extraordinariness:

“The old woman was a mistake perhaps, but she is not what matters! The old woman was only an illness.... I was in a hurry to overstep.... I didn’t kill a human being, but a principle!”

Raskolnikov further justifies his murder by asserting that Napoleon—his archetype of the extraordinary man—would have committed the same heinous act without a second thought if not for his privileged upbringing:

“What if it were really that?” he said, as though reaching a conclusion. “Yes, that’s what it was! I wanted to become a Napoleon, that is why I killed her.... Do you understand now? […]

It was like this: I asked myself one day this question—what if Napoleon, for instance, had happened to be in my place, and if he had not had Toulon nor Egypt nor the passage of Mont Blanc to begin his career with, but instead of all those picturesque and monumental things, there had simply been some ridiculous old hag, a pawnbroker, who had to be murdered too to get money from her trunk (for his career, you understand). Well, would he have brought himself to that if there had been no other means? Wouldn’t he have felt a pang at its being so far from monumental and... and sinful, too? Well, I must tell you that I worried myself fearfully over that ‘question’ so that I was awfully ashamed when I guessed at last (all of a sudden, somehow) that it would not have given him the least pang, that it would not even have struck him that it was not monumental... that he would not have seen that there was anything in it to pause over, and that, if he had had no other way, he would have strangled her in a minute without thinking about it! Well, I too... left off thinking about it... murdered her, following his example.”

But even though he commits not one but two murders, Raskolnikov vacillates between dubbing himself an extraordinary man and calling himself a coward and fool. We see in his confession to his friend, Sonia, that he behaved as we surmised: his main goal for murder was to prove himself extraordinary, and he became single-mindedly caught up in this burden of proof:

If I worried myself all those days, wondering whether Napoleon would have done it or not, I felt clearly of course that I wasn’t Napoleon. I had to endure all the agony of that battle of ideas, Sonia, and I longed to throw it off: I wanted to murder without casuistry, to murder for my own sake, for myself alone! I didn’t want to lie about it even to myself. It wasn’t to help my mother I did the murder—that’s nonsense—I didn’t do the murder to gain wealth and power and to become a benefactor of mankind. Nonsense! I simply did it; I did the murder for myself, for myself alone, and whether I became a benefactor to others, or spent my life like a spider catching men in my web and sucking the life out of men, I couldn’t have cared at that moment. […] I wanted to find out then and quickly whether I was a louse like everybody else or a man. Whether I can step over barriers or not, whether I dare stoop to pick up or not, whether I am a trembling creature or whether I have the right...

The Apologia

So how does Raskolnikov’s philosophy relate to Christianity and to negative apologetics? I am certainly not arguing that a belief in God is the only logical way to avoid becoming a murderer. Instead, I offer a few ways in which Raskolnikov’s worldview highlights the goodness of Christianity (or of theism in general) by their marked contrast:

The identity of the “extraordinary man.” To Raskolnikov, Napoleon is the archetype of the extraordinary. The extraordinary man is a “destroyer”; he breaks moral laws to “lead [the world] to its goal.” Unlike Hegel’s world-historical figure, Raskolnikov’s focus is not on the progression of world history or the fulfillment of a world goal but rather on the action of lawbreaking when defining his extraordinary man. Further, he doesn’t state that the extraordinary man might have to commit a necessary evil to reach a greater good; he states that a defining factor of the extraordinary man is his courageous criminality (“The second category all transgress the law”).

Part of this statement may ring true for us. We know ourselves to be relatively powerless against the world, only able to wrest power through rare blessings such as genius, through hard-earned and fickle worldly success, or through morally questionable means of subjugating others. Imagine if, right this very minute, you were to attempt becoming a major player on the world stage— how would you even begin? The task is so vast as to be nearly hopeless, and Raskolnikov knows it.

Here is where Christianity offers hope. The bloodthirsty tyrant, though he may be powerful enough to rule over the little man and bend nations to his will, is not worthy of emulation in God’s eyes. Christianity dethrones the power-hungry, morally compromised man to place a perfectly good and all-powerful person in his place: Jesus Christ. Jesus never succumbs to evil, but rather conquered evil with loving self-sacrifice. In Christianity, perfect adherence to moral law isn’t a defining characteristic of the weak but of God alone: Jesus practiced unflinching obedience to his Father’s will to save an undeserving people.

Christianity’s extraordinary man is the Almighty God— so powerful as to render Napoleon insignificant by comparison and so good as to give us hope in redemption and triumph over the sufferings of this earth. If the Christian God was good but not powerful, he could not stand up to evil. If He was powerful but not good, he might resemble Raskolnikov’s extraordinary man. Thank goodness that He is both.

The ultimate goal of the world. Raskolnikov describes the extraordinary man’s ultimate aim as “mov[ing] the world and lead[ing] it to its goal.” But what goal is that? At one point, he says that the goal is “[f]reedom and power, and above all power! Over all trembling creation and all the ant-heap!” But whether he is speaking of individual freedom, freedom for all extraordinary men (for the ordinary men getting trampled on the way to freedom are certainly not free), or some vague sort of societal freedom, we never find out. Raskolnikov himself hasn’t formulated his theory well enough to tell us, though his own ambitions are purely selfish. Even if he were concerned with the world at large, how can anyone devote their lives in working towards a goal if they do not know what the goal is (or who the goal-maker is, and therefore whether the goal might be good or bad)?

Christianity tells us that God has a plan for the world and and for each of us as individuals: we are “called according to his purpose” with plans to “give [us] hope and a future.” The fate of this world, its success or failure, do not ultimately rest in our hands. God assumes sovereign control over the world, yet we can contribute to His plan in clear and achievable ways by following the many commands He has given us: the ten commandments, the Great Commission, and so on. We neither bear the full burden of responsibility that the extraordinary men do, nor are we excluded from contributing to world progress like the ordinary men are.

Moral law. No matter how hard he tries, Raskolnikov can’t obliterate the existence of moral laws. He marks a man who transgresses moral law as extraordinary, yet he still identifies such a man as a transgressor. Even Raskolnikov himself can’t escape his realization that murder is wrong, as evidenced by his constant self-justification and his descent into physical illness and delusion following the murder. Whether you call it a collective conscience, a moral instinct, or the laws of a Lawgiver, it exists outside and above man. All the intellectual gymnastics or soul-numbing evil in the world cannot obliterate it. Man can choose to align himself with the unmovable Law or not, but he is not the determiner of good versus evil.

I like to think of absolute morality as similar to mathematical proofs: their truth is fixed across time, space, and circumstance, and they remain true and uncompromising whether we accept them or not. As Francis Schaeffer beautifully writes, without an absolute moral standard, we cannot judge anything as right or wrong, merely different (including Raskolnikov’s murders):

If there is no absolute moral standard, then one cannot say in a final sense that anything is right or wrong. By absolute we mean that which always applies, that which provides a final or ultimate standard. There must be an absolute if there are to be morals, and there must be an absolute if there are to be real values. If there is no absolute beyond man's ideas, then there is no final appeal to judge between individuals and groups whose moral judgments conflict. We are merely left with conflicting opinions.2

There are so many other ways to connect this rich novel to Christianity and to explore the differences between Raskolnikov’s philosophical influences (Marquis de Sade, Hegel, etc.) and Christian theism. I plan to continue with my march through church history and my academic dissection of apologia, however I will publish a post on “negative apologetics” every once in awhile in the hopes that brilliantly written stories will point us to theism in unexpected and nuanced ways.

Dostoevsky, Fyodor. (2001). Crime and Punishment. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved March 1, 2024 from https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2554/2554-h/2554-h.htm

Francis A. Schaeffer, How Should We Then Live?: The Rise and Decline of Western Thought and Culture, 50th L’Abri Anniversary Edition. (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2005), 145.

Photographs of Times Square: https://unsplash.com/photos/people-in-street-at-nighttime-hJwLoCI1TmA and Columbia University: https://unsplash.com/photos/a-group-of-people-standing-in-front-of-a-building-Y__v0BO0Sx0