Today’s post leads us on a path of artistic discovery linking the composers George Frideric Handel and Ludwig van Beethoven, the author Milan Kundera, and the character Jephthah in the Old Testament Book of Judges. They are all inextricably linked by the theme of predestination or “fate.”

The first step in our path is the novel that introduced me to Beethoven’s last complete musical composition: The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Czech author Milan Kundera. For those who haven’t read this novel, you must— it was a favorite of mine prior to my conversion to Christianity. Kundera sets his vividly realistic characters in the Prague Spring and muses on philosophy amidst his storytelling, lending his characters intellectual depth and complex (and often conflicting) worldviews. Although Kundera references Christianity several times, this is most certainly not a Christian novel: it is at times explicit and pulls heavily from Nietzsche.

The novel’s main character, Tomas, is superficially defined as a surgeon, a husband, and an adulterer. Similar to Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov, Tomas provides us with excellent material for negative apologia. Throughout the novel, Tomas’s notable life events are marked by the phrase “Es muss sein,” or “It must be,” which is taken from the fourth movement of Beethoven’s final composition titled “The Difficult Decision.” Kundera explores the role of chance and predestination in Tomas’s fate, with Tomas’s “It must be” superficially resembling Jesus’s “not my will, but yours be done.” But when we dig beyond the surface, we find in Tomas the antithesis to the duty-bound Jesus: Tomas is a man who is not only ruled by the desires of his flesh but a man who submits to them as inescapable fate.

Beethoven’s String Quartet and Es Muss Sein

Before we go any further, I must explain to you the original significance of “Es muss sein” and its relation to Beethoven’s last composition. Beethoven’s final complete composition was the String Quartet No. 16 in F major, Op. 135. It is divided into four movements; the first three are named after the tempo, or speed, at which they should be played: Allegretto (moderately fast), Vivace (fast and lively), and Lento assai, cantante e tranquillo (very slow with a singing and calm tone).

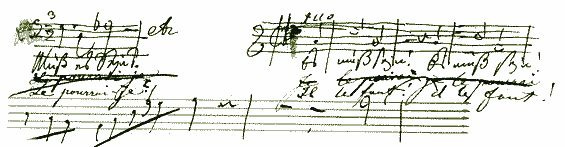

The fourth movement is titled "Der schwer gefasste Entschluss" or “the difficult decision.” Other translations replace the word “difficult” with “sober” or “heavy.” In the original manuscript, Beethoven penned the phrase “Muss es sein?” underneath the slow, solemn portion of the fourth movement (Grave, ma non troppo tratto) and wrote “Es muss sein!” underneath the faster, more cheerful-sounding reply (Allegro). These two phrases are German for “Must it be?” and “It must be!”

For the reader with plenty of time, here is the full version of the string quartet. For the reader with thirty seconds, here are the five measures under which “Muss es sein?” and “Es muss sein!” were written.

Handel as the Origin of Es Muss Sein

Why did Beethoven write these phrases under this piece? Was he contending with the end of his life and career, or with a Tomas-like conflict between desires? Kundera offers his hypothesis that Beethoven was referring to metaphysical gravity:

Unlike Parmenides, Beethoven apparently viewed weight as something positive. Since the German word schwer means both difficult and heavy, Beethoven's difficult resolution may also be construed as a heavy or weighty resolution. The weighty resolution is at one with the voice of Fate ( Es muss sein! ); necessity, weight, and value are three concepts inextricably bound: only necessity is heavy, and only what is heavy has value.

This is a conviction born of Beethoven's music, and although we cannot ignore the possibility (or even probability) that it owes its origins more to Beethoven's commentators than to Beethoven himself, we all more or less share, it: we believe that the greatness of man stems from the fact that he bears his fate as Atlas bore the heavens on his shoulders. Beethoven's hero is a lifter of metaphysical weights.

Another scholar offers another explanation based on the connection between Beethoven and the composer Handel1. As early as 1796, Beethoven composed variations for cello and piano and quoted from the “Hallelujah” chorus of Handel’s Messiah. Beethoven respected Handel as a composer, urging his pupil in an 1819 letter to “not forget Handel’s works, as they always offer the best nourishment for your ripe musical mind.” He referred to Handel as a “great man” and “the greatest composer that ever lived” and owned several volumes of his music. All this to say that Beethoven would have known Handel’s work intimately.

So how is this particular quartet tied to Handel? Handel’s last major composition, the oratorio Jephtha (called an oratorio instead of an opera because it is performed in an orchestral setting rather than as musical theater), opens with the recitative “It must be so.” Further, the notes accompanying these words (A-C-B♭-G) closely resemble the final movement of Beethoven’s Op. 135 (A-C-G), albeit with one note missing. If you have the time, listen to Jephtha here (the famous opening line is at the seven minute mark) or read the lyrics here.

Handel’s oratorio depicts the story of the Old Testament commander Jephthah from the Book of Judges. Jephthah, the son of a prostitute and a married man, is driven from his homeland by brothers who deny him an inheritance because of his birth. Jephthah flees, but his father’s clan and the Israelites are later plunged into war against the Ammonites, and they ask for Jephthah’s help. Jephthah agrees to serve as their commander in battle and vows to God that if he is granted military victory, he will make a burnt offering of the first thing to emerge from his home upon his return (Judges 11:30-31, NIV):

And Jephthah made a vow to the Lord: “If you give the Ammonites into my hands, whatever comes out of the door of my house to meet me when I return in triumph from the Ammonites will be the Lord’s, and I will sacrifice it as a burnt offering.”

Jephthah’s vow works: he defeats the Ammonites because “the Lord gave them into his hands” (Judges 11:32, NIV). But upon returning home to celebration and song, who emerges from Jephthah’s house but his only child:

When he saw her, he tore his clothes and cried, “Oh no, my daughter! You have brought me down and I am devastated. I have made a vow to the Lord that I cannot break.”

Jephthah’s daughter says “do to me just as you promised […] but grant me this one request”: to “roam the hills and weep” for two months to mourn that “I will never marry.” She returns in two months, as promised, having kept her vows of chastity as an unmarried woman — and then the Bible notes that Jephthah “did to her as he had vowed.”

The Bible doesn’t explicitly state what happened here, leading some scholars to believe that she was given to the tabernacle as a servant instead of sacrificed as a burnt offering, given the focus on her chastity and God’s deeming of human sacrifice as “abomination” and “sin” elsewhere (Jeremiah 32:35, NIV). Handel seems to favor this interpretation and reworks the ending in his oratorio, with Jephthah’s daughter meeting not death but rather becoming a chaste servant of God:

Rise, Jephtha, and ye rev'rend priests, withhold

The slaught'rous hand. No vow can disannul

The law of God, nor such was its intent

When rightly scann'd; yet still shall be fulfilI'd.

Thy daughter, Jephtha, thou must dedicate

To God, in pure and virgin state fore'er

Back to Kundera’s Tomas…

So now we know that the phrase “Es muss sein” made its way from Handel’s artistic interpretation of Judges 11 to Beethoven’s musical representation of weightiness and finally ended up at Tomas’s feet. Tomas, one of the main characters in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, is a notorious womanizer and accomplished surgeon. He meets Teresa, a younger woman who loves him dearly, but he cannot (and will not) relinquish his philandering even after their marriage. After Tomas and Teresa move from Prague to Switzerland and Tomas begins a new job in a local hospital, Teresa begins to have terrible nightmares about his infidelity. Soon enough, she writes a goodbye letter to Tomas and returns to Prague alone. In response, Tomas feels a strong and unbearable sense of “compassion” towards her— defined by Kundera as “emotional telepathy”— and his compassion drives him to reunite with her. When he gives his resignation to the hospital director, he explains it only with the phrase “Es muss sein”:

He kept warning himself not to give in to compassion, and compassion listened with bowed head and a seemingly guilty conscience. Compassion knew it was being presumptuous, yet it quietly stood its ground, and on the fifth day after her departure Tomas informed the director of his hospital (the man who had phoned him daily in Prague after the Russian invasion) that he had to return at once. He was ashamed. He knew that the move would appear irresponsible, inexcusable to the man. He thought to unbosom himself and tell him the story of Tereza and the letter she had left on the table for him. But in the end he did not. From the Swiss doctor's point of view Tereza's move could only appear hysterical and abhorrent. And Tomas refused to allow anyone an opportunity to think ill of her. The director of the hospital was in fact offended. Tomas shrugged his shoulders and said, Es muss sein. Es muss sein.

It was an allusion. […] This allusion to Beethoven was actually Tomas's first step back to Tereza, because she was the one who had induced him to buy records of the Beethoven quartets and sonatas. The allusion was even more pertinent than he had thought because the Swiss doctor was a great music lover.

Smiling serenely, he asked, in the melody of Beethoven's motif, Muss es sein?

Ja, es muss sein! Tomas said again.

But like many of us, Tomas is unsure of even his strongest emotions. He is overcome by the strength of his compassion but he cannot predict its duration nor can he predict the outcome of his life should he obey or disobey it. Tomas is ruled by two conflicting desires which he cannot control: the flesh-driven desire for adultery and the compassion-driven desire to return to his wife.

Es muss sein! Tomas repeated to himself, but then he began to doubt. Did it really have to be? Yes, it was unbearable for him to stay in Zurich imagining Tereza living on her own in Prague.

But how long would he have been tortured by compassion? All his life? A year? Or a month? Or only a week? How could he have known? How could he have gauged it?

Any schoolboy can do experiments in the physics laboratory to test various scientific hypotheses. But man, because he has only one life to live, cannot conduct experiments to test whether to follow his passion (compassion) or not.

Even many years later, after Tomas declared “It must be!” and returned to Prague for Teresa, his mind plays tricks on him and belittles his decision. Lacking a proper concept of God-ordained predestination, his concept of fate is frail, and his interpretation of his marriage flits between necessity and coincidence:

Leaving Zurich for Prague a few years earlier, Tomas had quietly said to himself, Es muss sein! He was thinking of his love for Tereza. No sooner had he crossed the border, however, than he began to doubt whether it actually did have to be. Later, lying next to Tereza, he recalled that he had been led to her by a chain of laughable coincidences that took place seven years earlier […] and were about to return him to a cage from which he would be unable to escape.

The Negative Apologia

Tomas is the perfect example of the man ruled by flesh: even if he were to follow all of his desires, they would lead him in completely different directions. One desire led him to destroy his marriage, and the other led him back to his wife— yet he does not remain faithful upon his return. He realizes what many Christians know to be true: that, despite being both an intellectual and a surgeon, he cannot control his own flesh with his own mind. It would take something higher, weightier, and more powerful than himself to control his desires. Tomas thinks that this is fate, the “Es muss sein,” and he surrenders to it.

But even though Tomas surrenders, we see that he isn’t fully at ease; how could he be, when he doesn’t know if fate is benevolent or where it will lead him? Uncertainty is something that all Christians must deal with when submitting to God, but at least we know that God is perfectly good and all-powerful and therefore possesses the nature and capability to bring about good ends. Even those who do not believe in God must harbor a healthy distrust in themselves, recognizing that we can easily lead ourselves astray due to our human naivete, imperfection, and incompetence. Believers in secular, materialistic determinism must further surrender the illusion of free agency in addition to surrendering the meaning behind sequences of events masquerading as romanticized fate.

Timothy Keller, the Presbyterian pastor and apologist, gave a brilliant sermon on a very similar subject: expressive individualism, or following our heart’s desires, won’t permit us to discover a stable, enduring, and true self which we crave. Even our deepest desires are naturally contradictory and changeable. And even if we could manage to satisfy all of them, we wouldn’t feel satisfied— at least, not for long. Dostoevsky’s horrid and unlikable character in Notes from the Underground echoes this same phenomenon:

Now I ask you: what can be expected of man since he is a being endowed with strange qualities? Shower upon him every earthly blessing, drown him in a sea of happiness, so that nothing but bubbles of bliss can be seen on the surface; give him economic prosperity, such that he should have nothing else to do but sleep, eat cakes and busy himself with the continuation of his species, and even then out of sheer ingratitude, sheer spite, man would play you some nasty trick. He would even risk his cakes and would deliberately desire the most fatal rubbish, the most uneconomical absurdity, simply to introduce into all this positive good sense his fatal fantastic element. It is just his fantastic dreams, his vulgar folly that he will desire to retain, simply in order to prove to himself--as though that were so necessary-- that men still are men and not the keys of a piano, which the laws of nature threaten to control so completely that soon one will be able to desire nothing but by the calendar. And that is not all: even if man really were nothing but a piano-key, even if this were proved to him by natural science and mathematics, even then he would not become reasonable, but would purposely do something perverse out of simple ingratitude, simply to gain his point. And if he does not find means he will contrive destruction and chaos, will contrive sufferings of all sorts, only to gain his point!

We might not relate to Dostoevsky’s harsh depiction of humanity or to Tomas’s adultery. But we can certainly relate to the depictions of human frailty, changeability, and self-contradiction. We can also see in Tomas the recognition of something higher: to him an impersonal and untrustworthy fate and to us the sublime God. Tomas, Beethoven, Handel, and Jephthah are preparing us for the moment when we will ask God with trepidation: “Must it be?” and He shall reply joyfully: “It must be!” Let us pray that we will shout that with Him in unison.

Silverman, G. (2003). New Light, but Also More Confusion, on “Es muss sein.” The Musical Times, 144(1884), 51–53. https://doi.org/10.2307/3650701