The M.D., the Ph.D., and the Doctor of the Church

Meet Athanasius, the first of 37 Catholic Doctors.

Scholars as Doctors

I’m slowly getting used to the look of polite disappointment on people’s faces when they realize that I am a computer-and-big-data type of “doctor” rather than a medical doctor. It’s fair enough— when the going gets rough, I’d rather know someone who could save my life rather than someone who does linear algebra in R.

Because I’ve always lived near a university, I am accustomed to people being excited about my work instead of wanting to fall asleep or run away at the first whisper of “research.” But since marrying my husband, I am continually humbled by his small Midwestern hometown. Out there, if you’re not a “doctor doctor,” nobody cares. I might as well lock myself in my ivory tower and scribble tomes of gibberish for the rest of my life.

If I were to ask you who values a doctor of philosophy, would your first answer be the Christian church? Those whose impression of Christianity is formed by American television wouldn’t even think that Christians valued medical doctors, much less someone with a less “practical” vocation. But even a cursory glance into church history shows what a critical role philosophers, teachers, and scholars played in the early church. In addition to the many Christian scholars we’ve already learned about, today’s apologist was formally deemed a “Doctor of the Church” by Roman Catholic communion in the late 1200s.

Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, was the first Doctor of the Church, a title given posthumously to those who made significant contributions to theology and doctrine. According to Pope Benedict XIV, there are three formalized prerequisites to earning this title: eminens doctrina (excellent doctrine), insignis vitae sanctitas (holiness or sanctity), and ecclesioe declaratio (declaration by the pope or council). While I’m drawing a tentative parallel between this doctorate and the modern academic, Doctor of the Church is a rare and spiritually oriented honor which is reflective of a life’s work. Church Doctors obviously aren’t comparable to secular degree recipients like myself; they received a great credit for spiritual service.

Athanasius and the Great Persecution

Although Athanasius is a Doctor of the Church, he (like all of the other apologists we have studied) experienced his fair share of persecution. Athanasius lived during the “Great Persecution,” the last and most severe persecution in the early 300’s Roman Empire. During this time, the legal rights of Christians were redacted and Christians were ordered to sacrifice to pagan gods. Eusebius describes the first Roman decree against the Christians1:

It was the nineteenth year of Diocletian's reign and the month Dystrus, called March by the Romans, and the festival of the Saviour's Passion was approaching, when an imperial decree was published everywhere, ordering the churches to be razed to the ground and the Scriptures destroyed by fire and giving notice that those in places of honour would lose their places, and domestic staff, if they continued to profess Christianity, would be deprived of their liberty. Such was the first edict against us. Soon afterwards other decrees arrived in rapid succession, ordering that the presidents of the churches in every place should all be first committed to prison and then coerced by every possible means into offering sacrifice.

I am writing from America, where Christians enjoy vast liberties of freedom of expression and public worship. As with any blessing we have grown accustomed to, we easily forget to thank God for our privilege— and to forget Christianity’s history of persecution and the modern-day instances of persecution in Iran, China, North Korea, and many other Asian and African countries.

Despite the anti-Christian laws, Athanasius spent much of his life combatting the heresy of Arianism, arguing against it in the Council of Nicaea. He was banished twice by Roman emperors who supported the Arians and he lived in monasteries during his banishments where he continued his work.

The Arian Heresy

The key heresy in Arian theology is this: it does not recognize the Son as fully God or as coeternal with the Father (in other words, the Son was begotten by the Father and did not always exist). Though Arianism is named after the Alexandrian priest Arius, the roots of Arianism are thought to reside with Paul of Samosata, (Bishop of Antioch in the 260s), our old friend Origen, and the pagan philosopher Aristotle.2

In some ways, Arianism is the definition of a non-Biblical yet well-meaning theology. One of its motives was to preserve monotheism, especially in a world where Christians were wrongly accused of polytheism because of the Trinity. But as noted by one scholar, this desire went awry3:

[T]he God whom the Arians declare to be ‘One’ is not the Living God of the Bible, but rather the Absolute of the philosophical schools. Arianism […] had no conception of a God who acts in history in creation, election, self-revelation, redemption, and sanctification; its God is absolutely transcendent, unknown and unknowable, infinite and immutable, without beginning or origin, One who cannot touch the life of the world in any way except through a created intermediary. […] The monotheism of the Arians is philosophical and not biblical.

Imago Dei and the Incarnation

Athanasius devoted much of his career to combatting Arianism. He wrote an Apology against the Arians before he was banished by Emperor Constantius, but we will focus on his most famous work here: The Incarnation of the Word of God.

In this work, Athanasius makes a few offensive arguments (offensive as in the opposite to defensive, not offensive as in offending the sensibilities), addressing both the Jews’ refusal to acknowledge the foretelling of Christ’s incarnation in the Old Testament and the Gentiles’ idolatry. But his writing is largely focused on acclaiming Christianity, particularly on explaining why Christ’s incarnation was necessary to save lost souls in a wayward world: “thus by what seems His utter poverty and weakness on the cross He overturns the pomp and parade of idols, and quietly and hiddenly wins over the mockers and unbelievers to recognize Him as God.”

Athanasius first speaks of why Christ took human form:

He has not assumed a body as proper to His own nature, far from it, for as the Word He is without body. He has been manifested in a human body for this reason only, out of the love and goodness of His Father, for the salvation of men.

I often hear Christians say that we are “made in the image of God” in reference to our physical bodies. Women sometimes say this as an attempt to dissuade makeup or plastic surgery and to promote an appreciation of one’s physical self. But if you apply this verse to our material bodies, it doesn’t make much sense, for God is immaterial. It is more precise to say that imago dei refers (in part) to our personhood rather than our human body or visual appearance.

Dr. Michael Heiser describes imago dei in great detail here; in summary, we are “imagers” of God. We are His representatives on Earth tasked with stewarding His creation; this is why Genesis 1 follows the imago dei statement with the dominion mandate.

It may seem like I am making a tangential point here, but I think that a proper understanding of imago dei goes hand-in-hand with a proper understanding of the immaterial Word and the Son’s identity as God. We weren’t made in the visual image of a humanoid Jesus; rather He brought matter into existence as the immaterial Creator:

[T]o deny that God is Himself the Cause of matter is to impute limitation to him, just as it is undoubtedly a limitation on the part of the carpenter that he can make nothing unless he has the wood. How could God be called Maker and Artificer if His ability to make depended on some other cause, namely on matter itself? If he only worked up existing matter and did not Himself bring matter into being, He would be not the Creator but only a craftsman.

Intelligent Design?

I was surprised to find how many of Athanasius’ arguments about the incarnation of Christ are relevant to the philosophy of Science. Take this, for example:

For instance, some say that all things are self-originated and, so to speak, haphazard. The Epicureans are among these; they deny that there is any Mind behind the universe at all. This view is contrary to all the facts of experience, their own existence included. For if all things had come into being in this automatic fashion, instead of being the outcome of Mind, though they existed, they would all be uniform and without distinction. In the universe everything would be sun or moon or whatever it was, and in the human body the whole would be hand or eye or foot. But in point of fact the sun and the moon and the earth are different things, and even within the human body there are different members, such as foot and hand and head. This distinctness of things argues not a spontaneous generation but a prevenient Cause; and from that Cause we can apprehend God, the Designer and Maker of all.

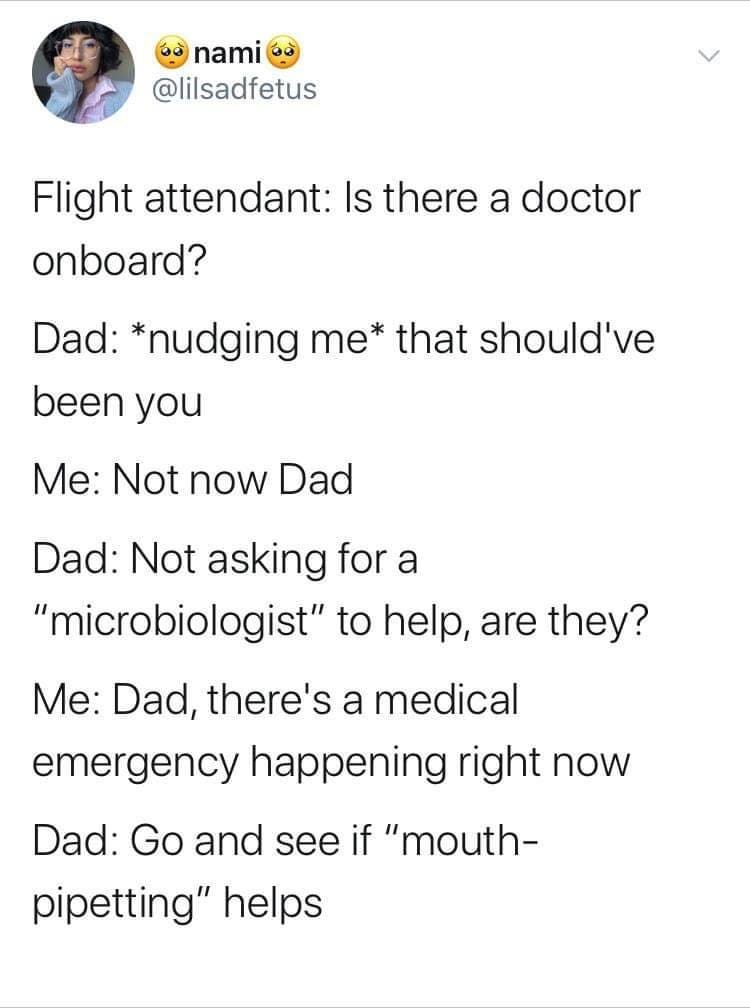

Interestingly, Athanasius correctly aligns self-originated matter with randomness, as does modern-day Neo-Darwinism. But instead of making the typical Intelligent Design argument that randomness is not a creative force, he makes a similar argument that randomness would produce “uniform” things lacking in distinction. Athanasius seems to be making an entropic-like claim that chaos and randomness will reduce order and distinctiveness to homogeneity.

I’ve made a vastly over-simplified cartoon below to grasp at what Athenasius meant. If you have another interpretation of his quote, please leave it in the comments below!

Next time, we will continue with more of the Incarnation. In the meantime, consider this: Athanasius is an excellent example of how “academic” theology has particular and often unexpected downstream effects. What theological beliefs are underpinning your understanding of the material world, be that your understanding of your own body or your understanding of evolution / I.D. / creationism?

Tidbits:

The Doctor of the Church designation is far from an ex cathedra stamp of approval on the authority, or even validity, of every single word a theologian has penned.

Four women have posthumously received this honor since the 1970s: Hildegard of Bingen, Teresa of Avila, Catherine of Siena, and Therese of Lisieux.

Eusebius, of Caesarea, Bishop of Caesarea, approximately 260-approximately 340. The History of the Church from Christ to Constantine. Baltimore :Penguin Books, 1965. Retrieved from https://facultystaff.richmond.edu/~wstevens/history331texts/eusebius.html

Pollard, T. E. “THE ORIGINS OF ARIANISM.” The Journal of Theological Studies 9, no. 1 (1958): 103–11. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23953621.

Ibid., 104.